İhsan Raif: a woman with a pen and a pillow in Istanbul

"İhsan Raif was a pioneer poet who used a novel style in her poetry. She is also the author of the lyrics of some quite well-known songs in Turkey. She composed music and sang classical Turkish tunes while masterfully playing the piano. Unfortunately, most people who still sing these songs today do not know that the lyrics belong to her."

18 Ocak 2021 11:50

Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies -for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Woman must put herself into the text -as into the world and into history- by her own movement.

Hélène Cixous[1]

A fine summer evening in Istanbul on June 9, 1910… Ahmet Samim, the chief columnist of the opposition newspaper, Sada-yı Millet left the print house with his friend Fazıl Ahmet (Aykaç); they were headed to the Galata Bridge on their way to a dinner in Kuruçeşme. As they walked by the Greek bakery in Bahçekapı behind the New Mosque, two shots were heard. First bullet penetrated Ahmet Samim’s neck from behind. As he fell to the ground, a second bullet hit him on his back. His friend Fazıl Ahmet, although in a state of shock, managed to find shelter inside the Greek bakery. Ahmet Samim was the second journalist/writer assassinated in the last 14 months in Istanbul. Before him, Hasan Fehmi, the editor in chief of another newspaper, Serbesti, was killed on the Galata bridge on April 6, 1909. These were turbulent times in the wake of a major social and political transformation.

Hasan Fehmi and Ahmet Samim were both in opposition to the policies of the Committee of Union Progress (CUP) that became increasingly powerful during the time leading to the proclamation of the Second Constitutional Monarchy in 1908. Ahmet Samim had already received threatening letters prior to his assassination. With vivid memories of Hasan Fehmi’s assassination, his friends were fearing for his life. Ahmet Samim’s assassination is described in a period novel titled Hüküm Gecesi authored by Yakup Kadri (Karaosmanoğlu). A few days before his assassination, Ahmet Samim received an invitation from the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Ottoman state, Talat Bey. During this visit, Talat Bey offered him a position in the state in an effort to co-opt him. Offended by this offer, Ahmet Samim rejected him by saying that he was happy to have a clear conscience for not associating with the CUP government. It is impossible not to take note of the pattern of these assassinations in Istanbul. Hrant Dink, an Armenian journalist/writer and a beloved friend, who was assassinated on January 19, 2007 in front of the office of his newspaper Agos in Istanbul was also invited to the Governor’s Office shortly before his assassination, indicative of a historical pattern for such crimes of the deep state. Ahmet Samim’s assassination had a huge impact on the literary circles in Istanbul. These were turbulent times indeed.

It was about the same time that a new journal for women called Mehasin was being published in Istanbul. It was published between September 1908 and November 1909, only twelve issues altogether. İhsan Raif published three poems in the last three issues of this journal in 1909. These poems can be found in the comprehensive volume prepared meticulously by Cemil Öztürk that contains all the published and unpublished poems (from her Notebooks) of İhsan Raif. There is also an earlier, less comprehensive book on her poetry authored by Hüveyla Coşkuntürk. İhsan Raif’s first poem titled “Gel Gidelim” (Come, let’s go), published in September 1909 in the 10th issue of Mehasin, was an exuberant and inviting poem that ended with the verse: “Aşk kafidir, ver elini düşünme, gel gidelim” (Love is enough, give me your hand, do not think, come and let’s go). She was 32 years old. Her second poem (“Verem”), in the 11th issue, depicted a patient with tuberculosis. “Sonbahar” (Autumn) was the title of her third poem that was published in the last (12th) issue of Mehasin. The joy and zest for love and life, visible in her first poem, were replaced with expressions like “hüzn” (melancholy) and “matem” (mourning) in the last one. For a woman who was living in a city dominated by political conflicts among men, her fluctuations from joy to melancholy were hardly surprising. She was obviously living through her own struggles while seeking an inner dialogue through the act of writing. Her pen was probably her main if not the only point of reference all through her short life. Ironically, the 10th and 12th issues of Mehasin also contained poetic essays by Şahabettin Süleyman who would become İhsan Raif’s third husband a few years later. Although their encounter had already taken place on the pages of this journal for women, their partnership in life was about to be initiated in the pages of another journal called Rübab.

The main endeavor of this essay is to depict the turning points in İhsan Raif’s life against the background of the literary and political climate of her times in Istanbul. Given my academic foundation in Political Science, I did not venture into a study about her poetry. The focal point of my interest is rather the life and times of a female poet in my beloved city, Istanbul, in the final years of the Ottoman Empire. Throughout the essay, I hesitantly tried to translate only a few of her verses into English in an attempt to let her voice be heard. There is no doubt that it would be an invaluable contribution if her collected poems were translated into English.

Accounts about İhsan Raif’s life are mostly found in memoirs that were penned by male poets, essayists, and novelists of the era. Depicting the life of a woman in masculine accounts is like searching a needle in a haystack. Fortunately, she also used her pen generously. İhsan Raif was a pioneer poet who used a novel style in her poetry. She is also the author of the lyrics of some quite well-known songs in Turkey. She composed music and sang classical Turkish tunes while masterfully playing the piano. Unfortunately, most people who still sing these songs today do not know that the lyrics belong to her. Her most popular lyrics are the ones for the song titled “Kimseye Etmem Şikayet” (I do not complain to anyone). They are as follows (the original lyrics are followed by my translation to English):

Kimseye etmem şikayet

Ağlarım ben halime

Titrerim mücrim gibi

Baktıkça istikbalima

Perde-i zulmet çekilmiş

Korkarım ikbalime

I do not complain to anyone

I only cry for my condition

I tremble like a felon

When I look into my future

A curtain of darkness is drawn

I am afraid, over my prospect

The music for these words was composed by Kemani Sarkis Efendi Suciyan (1885-1943), an Armenian composer of Ottoman, Turkish classical music. This is a song that my ninety years old mother sings from her heart each time it plays on the radio or television. My mother always closes her eyes when she sings the words. Today, many people still sing the verses of this heart wrenching song without knowing anything about their female author. There are other such songs by İhsan Raif that are known popularly without any reference to her name.

I had used the verses of the above song in an opinion piece that I authored on the feeling of “angst” in Turkey in 2011, after a conference on Armenians of Diyarbakır organized by the Hrant Dink Foundation, in the hope that such conferences would lift the “curtain of darkness” drawn over Turkey’s past. To my regret, I had also failed to mention her name as the author of these lines, because, like most people, I did not know about her. I hope, this essay not only makes up for my past ignorance and negligence but also empowers women who can still identify with her life today.

A thirteen years old married woman

İhsan Raif was born in Beirut in 1877 as the daughter of Servet Hanım and Köse Mehmet Raif Paşa when her father was the mutasarrıf (provincial governor) of the Ottoman state there. Her father became a protégé of Midhat Paşa at the time of the latter’s Danube governorship. Midhat Paşa was an Ottoman statesman who played a key role in the preparation of the 1876 Constitution (Kanun-i Esasi) during the First Constitutional Monarchy. His relations with Sultan Abdülhamid were strained. In August 1880, Abdülhamid sent his aide-de-camp miralay (commander) Süleyman Bey to Beirut in order to transfer Midhat Paşa to Izmir on the steamship Izzettin. Köse Mehmet Raif was in Istanbul at that time. It was at this time that Köse Mehmet Raif’s harem was forced to travel along with Midhat Paşa aboard this ship through an Imperial Rescript. İhsan Raif was only three years old. While Midhat Paşa was put on trial at the Yıldız court for the murder of Sultan Abdülaziz, Abdülhamid decided to integrate Köse Mehmet Raif into his circle and appointed him as a Minister. It was at this time that Köse Mehmet Raif was promoted to become a Paşa as well. He was later appointed to be the governor of Adana.

İhsan Raif had four brothers and a sister. While her brothers had their education in good schools, İhsan Raif and her sister were home schooled during their father’s appointments in different provinces. While her father was the governor of Adana, she took classes from Muallim Danyal Efendi. While in Istanbul, she took private classes in French language and music. She excelled in playing the piano. She also took classes with Rıza Tevfik (Bölükbaşı), one of the most well-known poets at the time, who was a pioneer in exploring a new style in poetry.

When İhsan Raif’s father was appointed the Minister of Customs in 1888, the family moved back to Istanbul and into their newly completed five story mansion (konak) in Nişantaşı known as the Raif Paşa Konağı. Although most mansions of the era in this neighborhood were wooden, this konak was built with stones and hence, came to be known as Taş Konak (Stone Mansion). Today, it is one of the few buildings that survived the fires in Nişantaşı. The building was restored in 2010 and used as the local state office of the Şişli borough (Şişli Kaymakamlığı) until recently. In fact, the former Kaymakam of Şişli, Mehmet Öklü published a novel about the long time owner and resident of Taş Konak, İhsan Raif, in an attempt to revive her memory. Today, Taş Konak’s beautiful exterior stands in stark contrast with the surrounding shabby buildings in one of the most populated streets of Istanbul, namely Rumeli Street. Its well-poised edifice, pressed among multiple shops and fashion stores, constitutes a stark contrast with the ever present and messy traffic of honking cars and rushing pedestrians. Nevertheless, on a rare quite moment, Taş Konak can still turn heads with its resilient elegance…much like the way İhsan Raif Hanım must have turned heads with her legendary stature as she walked home to Taş Konak about one hundred years ago.

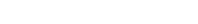

İhsan Raif as a young girl with an unidentified boy

(Taha Toros Archive, Istanbul Şehir University Library)

İhsan Raif was forced to marry her first husband when she was only thirteen years old. Her family was a well-known, wealthy family in Istanbul. The marriage resulted from a scheme planned by her first husband with the help of the domestic servants at Taş Konak. Her first husband, Mehmet Ali Bora, was allowed into the building one evening and climbed up the stairs and entered the room where İhsan Raif and her sister Belkis were present. He was planning to kidnap İhsan Raif but since the screams of the girls alerted the domestic servants, he left the building as fast as he entered and ran away. Finally, İhsan Raif was forced to marry Mehmet Ali Bora since he had seen her in the privacy of her room.

The encounter between a man and a woman (although İhsan Raif was only thirteen years old) in the privacy of a room when the woman was not accompanied by a male relative was enough to stain the reputation of a young girl. Women would soon express their frustration with such rules. In her comprehensive and detailed analysis of the women’s journals that were mushrooming at this time, Serpil Çakır mentions a letter from a reader, a young woman named Nedime Sârâ, to the newspaper Kadınlık (Womanhood) on April 3, 1914. After complaining about her mother’s conviction that a woman’s wish to get education is a “sign of apocalypse,” Nedime Sârâ wrote: “If a man accidentally sees us while we look out the window, we have to deal with our mothers for we would have no honor…all this offensive, all this rage, for what? For a man saw us –as they call it– unsecluded (namahrem).” (p. 86) İhsan Raif’s unsecluded exposure to Mehmet Ali Bora, indeed led to a kind of apocalypse, a tragic turning point in her life. Her father insisted that the only thing left to do under the circumstances was her to marry Mehmet Ali Bora who was an intruder in her life. Soon, İhsan Raif found herself aboard a ship sailing to Izmir with her new husband.

İhsan Raif arrived in Izmir as a thirteen years old married woman. She did not know the man by her side. She was in deep pain. Her inner voice and internal dialogue gave her strength during the next fourteen years of her life in Izmir. She was fourteen years old when she had her first son. She subsequently had a daughter and another son. After the family returned to Istanbul, İhsan Raif could no longer endure her husband’s misconduct. She was extremely unhappy. Her father accepted her plea to return home and soon she was divorced and settled back in Taş Konak with her daughter and her younger son (her older son stayed with her husband).

Soon, İhsan Raif got married for the second time. There is not much information about her second husband. He was apparently someone that her father knew. This marriage did not last very long. Cemil Öztürk (p. xii, ft. 6) maintains that her second husband’s name might be Fehim since Nezihe Muhiddin, a leading activist woman in Istanbul, referred to İhsan Raif as “İhsan Raif Fehime” in one of her texts. While some writers such as Mehmet Öklü depicted İhsan Raif as defiantly leaving her second husband because he demanded that she kissed his hand as a show of respect, others maintain that his second husband may have had a contagious disease (possibly tuberculosis) that led to their divorce. Since her aforementioned poem on tuberculosis was published in Mehasin by the end of 1909, it is possible to deduce that she might have been going through her short second marriage at that time. By the time her father Köse Mehmet Raif Paşa died in 1911, İhsan Raif was a 34 years old published poet who was divorced twice and living in Taş Konak in Istanbul. She was about to enter the blossoming literary circles in Istanbul. This was an entry that was intertwined with her encounter with the love of her life, Şahabettin Süleyman.

Şahabettin Süleyman and İhsan Raif: Love in the pages of Rübab

I began this essay with the assassination of Ahmet Samim in June 1910 since it was an event that had a big impact on the literary circles in Istanbul. The era after the Second Constitutional Monarchy was a lively literary era with flourishing new newspapers, and journals. Fecr-i Ati (Dawn of the Future) was a captivating literary movement led by a group of young and rising literary figures. They had their first meeting on March 20, 1909 in the publishing house of the Hilal newspaper in Cağaloğlu. Hilal print house was raided by the CUP government’s security forces in the aftermath of the 31 March incident (13 April 1909 according to the Gregorian calendar); a counter coup attempt triggered by Hasan Fehmi’s assassination and was suppressed by the forces loyal to the CUP. In his memoirs, Gençlik ve Edebiyat Hatıraları, Yakup Kadri described how the writers of Hilal had to escape from the back window of the print house.

Fecr-i Ati became the first literary group that published a literary manifesto on February 24, 1910. In this manifesto, while declaring their respect and appreciation for the former literary movement Edebiyat-ı Cedide and its journal Servet-i Fünun, they maintained that most members of this movement had lost touch with one another under the despotism of the government before 1908. Fecr-i Ati opted for a revival and outlook towards the future; offering a “green shade in this desert of science and literature.” Ahmet Samim, who was assassinated in less than four months after the publication of Fecr-i Ati’s manifesto, was among its twenty one signatories. Among the literary figures who signed this literary statement, there was Şahabettin Süleyman who later became İhsan Raif’s third husband and Fazıl Ahmet, who was with Ahmet Samim on the day of his assassination. Yakup Kadri, another key writer and a close friend of Şahabettin Süleyman, was also among those who signed it. While the literary world was revitalized with this new movement, İhsan Raif had just began to publish her poetry in Mehasin. In a few years, these men were about to become regular guests in the literary gatherings in her house.

Şahabettin Süleyman was a key literary figure within the Fecr-i Ati group. In Hüküm Gecesi, Yakup Kadri described how Ahmet Samim had developed almost a dependence to Şahabettin Süleyman and always wanted to be around him. Their literary discussions would mostly last until morning hours in various venues in Beyoğlu such as Nikoli Beerhouse and Sketing Bar, most likely a venue at the Skating Palace built in 1909. The expression “to go up to Beyoğlu” (Beyoğlu’na çıkmak) was used, much like today, implying an evening of invigorating fun. Ahmet Samim’s assassination had a big impact on all his friends in Fecr-i Ati. They grew more critical (albeit fearful) of the CUP. They also became increasingly affiliated with the opposition (muhalefet) against the CUP. In Hüküm Gecesi, Şahabettin Süleyman is depicted as rushing to the print house after hearing about Ahmet Samim’s assassination. While standing across from his friend’s corpse, Şahabettin Süleyman looked so pale that he was like a wax statue of himself. Fearing for his life, he said “now, they will come after us.” (p. 75) Şahabettin Süleyman, who was initially sympathetic to the CUP, began to publish essays against the CUP in opposition venues such as the Hakimiyet’i Milliye, Yeni Ses, and Muahede after the assassination of his beloved friend. He became the spokesman of the early opposition party named Fırka-i İbad which later joined Hürriyet ve İtilaf Fırkası.

Şahabettin Süleyman was such a leading Fecr-i Ati figure that the slogan he uttered “Art is personal and respectable” (Sanat şahsi ve muhteremdir) had become the slogan of this literary movement. According to Yakup Kadri’s memoirs (Gençlik ve Edebiyat Hatıraları), they believed that no one could tell a poet or a novelist what to write for this would be “as despotic as telling someone with blue eyes that his eyes will be black.” By 1912, Şahabettin Süleyman, a pioneer at heart, began to lead the publication of a new journal named Rübab (named after a musical instrument with strings akin to a lute). After the publication of the first issue on February 7, 1912, Rübab was published for over two years with more than one hundred issues. It was in the pages of Rübab, distinguished with its pink pages, that a new generation of literary figures who called themselves Nayiler (after the musical instrument Ney) was established. Nayiler was formed when Fecr’i Ati was losing its edge to nationalist writers. It was no longer adequate to define art as personal and respectable and there was increasing need to associate with more social and political causes. Ironically, it was Şahabettin Süleyman, a leading figure of the Fecr-i Ati who prepared the ground for the birth of the Nayiler in the pages of Rübab. As Halit Fahri (Ozansoy) put it in his memoirs, Edebiyatçılar Çevremde (p. 193), Şahabettin Süleyman described the distinguishing feature of the Nayiler as having “aheng-i derunî,” an inner harmony, an inner music akin to the music of Ney. Many key literary debates of the era took place in the pages of Rübab, reflecting the literary trends of the era.

It is obvious that Şahabettin Süleyman was a key figure in all of these literary circles. In fact, one of the key authors of the era, Hüseyin Rahmi (Gürpınar), who received his share of criticisms in Rübab, referred to Şahabettin Süleyman as “direktör literer” (literary director) and “eternal Don Quixote.” He was full of new ideas and never stopped to set new trends. Young generation of writers wanted to be around him. They visited him in the small office of the journal on Şeref Efendi Street in Cağaloğlu. Despite his popularity among the young writers, he did not lose touch with the older generation of writers. Even Rıza Tevfik, İhsan Raif’s tutor and a former CUP member of parliament who later joined the opposition, wrote in the pages of Rübab.

Şahabettin Süleyman was a daring writer. In 1908, he authored a play about a lesbian relationship titled Çıkmaz Sokak (Dead End Street) which led to his troubled relationship with the Ministry of Education and cost him his teaching job at Vefa İdadisi. In an informative article, Ayşe Duygu Yavuz (p. 1453) portrays how Çıkmaz Sokak was criticized fiercely from the angle of morality, and for containing “filth that gives one goose bumps” and “scars the consciences.” Şahabettin Süleyman loved the theatre and not only wrote but also acted himself in several plays. He led the life of a bohemian in Istanbul, writing, acting in plays, forming and leading literary movements and “going up to Beyoğlu” in the evenings. As his friend Halit Fahri wrote in his memoirs, Edebiyatçılar Geçiyor (p. 238): “Ah how we loved him! He was our brother, our master, our guide in literature.”

Rübab was not only a journal covering the debates of the era; it also triggered the relationship between İhsan Raif and Şahabettin Süleyman. İhsan Raif began to publish her poetry in the pages of Rübab in 1913. She was not the only woman writing in Rübab. In fact, there were 58 women who published poems and essays in this journal. The owner of the journal, Celal Nadir, had even published an essay in the 112th issue inviting women’s writing by indicating their wish for Rübab to be a venue for women (p. 26) as well. This was the time when İhsan Raif’s poems became noticeable among the young literary authors. Yakup Kadri (Gençlik ve Edebiyat Hatıraları) mentions how her poems right next to the essays of Şahabettin were intermingled in the pages of Rübab which symbolized the love that was about to be born between them. Soon, these essays and poems began to resemble declarations of love.

In Edebiyatçılar Geçiyor, Halit Fahri described how one Spring day Şahabettin Süleyman invited him along with Hakkı Tahsin to take a ferry along the Bosphorus. As they were in the ferry, a woman with a “beautiful figure akin to the old royals” whose face is covered by a thin veil passed in front of them. As she moved towards the women’s section of the ferry, she looked at Şahabettin Süleyman and smiled. Halit Fahri described this smile under her thin veil as beautiful as “the blossoming of a rose.” (p. 246). She left the ferry at the Yeniköy Pier. Later that day, Halit Fahri noticed that Şahabettin Süleyman was no longer his talkative self. He was not hearing the conversations of his friends around him either. His eyes were fixated on the soothing view of the Bosphorus as the three of them sat together. He was silent with twinkles of a different joy in his eyes. Şahabettin Süleyman was in love with İhsan Raif, whose beautiful smile was akin to the blossoming of a rose.

Literary gatherings at Taş Konak

The devastation of the First Balkan War had heightened the feelings of nationalism among the literary circles. İhsan Raif volunteered as a nurse in Hilal-i Ahmer (Red Crescent) during the war and wrote two poems inspired by this experience. (Öztürk, pp. 38-40). She also took part in the pioneer women’s meetings at Dârulfünun (Istanbul University) organized by the Müdafaa-i Milliye Cemiyeti Hanımlar Heyeti (Women’s Branch of the National Defense League) on February 8 and 15, 1913 in an effort to collect aid for the soldiers. The meeting room was filled with four to five thousand women. Those who could not find seats were gathered in the corridors and the garden. In this meeting, İhsan Raif read a patriotic poem titled “Feryad-ı Vicdan” (Scream of the Conscience). The poem was filled with motifs of war, willingness to die for the nation and revenge. This was also a time immediately after the raid on the Sublime Port (January 23, 1913), a coup d’etat led by members of the CUP such as Enver Bey. The Commander in Chief, Nazım Bey, was shot and killed during the raid and the government was forced to resign. The raid enhanced the powers of the CUP members such as Talat Bey and Enver Bey. From this point onwards, the earlier individual journeys in art and literature were being replaced by cries of Turkism, blood, and revenge.

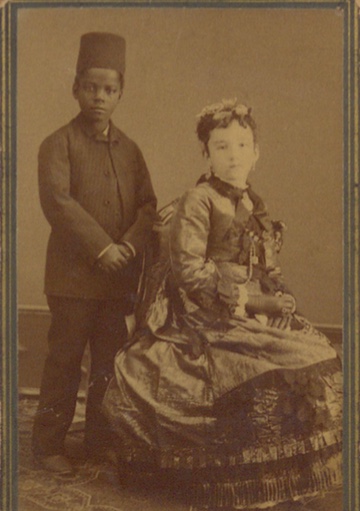

İhsan Raif and Şahabettin Süleyman

(Taha Toros Archive, Istanbul Şehir University Library)

The exact date of the marriage ceremony of İhsan Raif and Şahabettin Süleyman is not known. It was most likely a date at the end of 1913. İhsan Raif’s publication of a poem titled “Ey Firdevs-i Hayalim” (Oh my dream garden) in the pink pages of Rübab by mid-1913 was a manifestation of her love for Şahabettin Süleyman. (Öztürk, p. 231). In this poem, she used expressions like “üftadenim” (your desperate, passionate lover) and brought divine love down to earth by verses such as “Gözlerin Kur’ân-ı aşkımdır, kucağın cennetim” (Your eyes are the Qur’an of my love, your lap is my heaven). The music for these words was composed by Tanbûrî Hikmet Bey and is still performed today by various artists. The couple began to live at Taş Konak. According to Yakup Kadri, this marriage was the beginning of a new life for Şahabettin Süleyman. With the magic touch of İhsan Raif, Şahabettin Süleyman was transformed from a charismatic, bohemian writer with messy clothes to a well-dressed royalty. Soon, İhsan Raif’s first book of poems titled Gözyaşları was published. At this time, Taş Konak was becoming one of the key addresses for literary gatherings (edebiyat mahfilleri) in İstanbul. These gatherings were known by the name of their host İhsan Raif Hanım.

In both of his memoirs, Halit Fahri mentions Selahattin Enis, Fazıl Ahmet, Ruşen Eşref, Hakkı Tahsin, and himself as the regular guests at these literary gatherings at Taş Konak that convened a few evenings per week. Some of these guests were around Şahabettin Süleyman all through the days of Fecr-i Ati, Nayiler, and Rübab. It is obvious that, if Ahmet Samim was alive, he would have been a regular guest at Taş Konak as well. They were also joined by Yahya Kemal (Beyatlı) and İhsan Raif’s poetry tutor Rıza Tevfik. In Edebiyatçılar Çevremde (p. 257), Halit Fahri points to the similarities between these gatherings and the 17th century salon meetings in Paris by women called les précieuses, creating a refuge from the political turmoil of the times.

The guests would typically read their new poems and essays to each other in these gatherings while sipping the tasteful liquors offered by their host, İhsan Raif. Şahabettin Süleyman once read passages from his play titled Siyah Süs, a play that went missing without ever getting published. Şahabettin Süleyman was quite fond of the views of the French writer Charles Lalo on aesthetics. He was often seen walking around with Lalo’s book on aesthetics under his arm. While he was translating Lalo’s work, he read some passages in these gatherings. Sometimes, the readings would take long hours. One evening, when Ruşen Eşref read his travel memoirs to Kars and Batum for over an hour, Fazıl Ahmet ended up fainting in his armchair! (Edebiyatçılar Geçiyor, p. 26). Selahattin Enis, a regular guest at Taş Konak, and a writer whose style was compared to Émile Zola’s naturalism, famously read suggestive and risqué stories in these gatherings. These risqué stories would generate awkward moments making İhsan Raif lower her gaze with a mischievous smile on her lips while Şahabettin Süleyman and others would cough in a vain attempt to stop Selahattin Enis from reading any further.

The high point of the gatherings at Taş Konak were the moments when İhsan Raif read her poems, played the piano and sang her own songs as well as other classical Turkish tunes. Her legendary performance of Gülizar Peşrevi was the high point of these gatherings. The guests at Taş Konak were clearly mesmerized by her presence. Halit Fahri (Edebiyatçılar Geçiyor, p. 247) confessed that, like many other guests, he was virtually in love with her. He described how he was taken by her sight in one of his visits to Taş Konak when the domestic servant accidentally admitted him into the room where İhsan Raif was lying elegantly on her side on the gorgeous rug trying to prepare a bouquet of flowers with a pair of scissors in her hand. A sight, he though, that would inspire master painters… She immediately got up when she saw him with a friendly and impish smile.

On one occasion, Şahabettin Süleyman and Halit Fahri were working on the translation of Lalo’s book on aesthetics at Taş Konak. As they were focused on their work, Halit Fahri was startled with the glimpse of a hand by his side. He immediately thought it was the hand of Şahabettin Süleyman offering him some grilled chestnuts. He said that he did not want any. When he turned around, he realized that it was not Şahabettin Süleyman but İhsan Raif on his side. He was all hot on the face with embarrassment when İhsan Raif asked with a soft smile: “What is it that you do not want Halit Fahri Bey?” Halit Fahri mumbled: “Excuse me…chestnut…I already ate…a lot.” İhsan Raif smiled and said: “I was just reaching out for the ashtray!” (Edebiyatçılar Çevremde, p. 259). Such moments described in Halit Fahri’s memoirs portray these men’s awareness of the presence of a woman among them. They adored her manners, her intelligence as well as her physical beauty. She was older than most of them as well as eight years older than her husband, Şahabettin Süleyman. After all those literary discussions amongst all male writers and poems in the scruffy beerhouses of Beyoğlu, these men found themselves discussing literature in a fancy mansion, in the presence of a woman who was behaving like their equal. They saw her as royalty and respected her. Yet, they did not seem to know how to be friends with her. Semih Mümtaz S.’s depiction of İhsan Raif (Akşam, May 5, 1947) symbolized the way these men saw her. After praising the honesty of her writing, Semih Mümtaz S. described İhsan Raif as joyful, humorous, sensitive, well-mannered, tolerant, and as someone who “knew about the triumph of forgiving.”

These men also knew of Şahabettin Süleyman’s affair with a woman named Rana Dilberyan who had the nickname Virjini. She and Şahabettin Süleyman were already seeing each before his marriage to İhsan Raif. According to Halit Fahri (Edebiyatçılar Geçiyor, pp. 247-8), the affair between Rana Dilberyan and Şahabettin Süleyman apparently continued after the marriage and İhsan Raif was exasperated by the letters that Rana Dilberyan sent her.

Discriminatory remarks about Greek and Armenian women are quite common in the memoirs of these male literary figures. Non-Muslim women were portrayed as readily available for these men’s pleasures. Rana Dilberyan was a well known Armenian actress in the theater circles. She worked with the Binemeciyan theatre company and acted in one of the leading roles in the feature film Binnaz (1919) by Ahmet Fehim. There is no doubt that the portrayal of the social and political dynamics of this period in Istanbul would be incomplete without a thorough and distinct study into the dynamics of the lives of the non-Muslim women such as Rana Dilberyan. The references to non-Muslim women in the memoirs of literary men do not contain the respectful language that they employed towards İhsan Raif. Yet, as we will see below, the respect and adoration that İhsan Raif enjoyed did not last very long either.

Strikingly, all the accounts about the content of the discussions in these literary gatherings did not contain any referrals to the deportation of the Armenians of Istanbul on April 24, 1915, marking the Armenian Genocide. This is a silence that reflects the prevalent spirit of nationalism of the era and the competition even among the more individualist literary figures to reflect this spirit in their work. The deported Armenian men and women were members of the Istanbul intelligentsia. Surely, these literary figures must have known about them. Yet, not a word was uttered about this tragedy. Moreover, their silence was at times replaced by referrals to malicious intentions of the Greek and Armenian citizens who ostensibly joined the city wide celebrations of the Second Constitutional Monarchy (Edebiyatçılar Çevremde, pp. 231-232). The apparent lack of concern for the well being of their non-Muslim colleagues among the Turkish intellectuals undoubtedly reflected the ferocious Turkification of the city. Istanbul, a city that was legendary with its diversity and the coexistence of Muslims and non-Muslims, was becoming a Turkish and Muslim city. This transformation sadly scarred the city at many levels, namely in music, literature, arts, architecture and most importantly in its very spirit. An essay that upholds the life, poetry and music of a Turkish female poet who is also forgotten and not acknowledged today would be incomplete without mentioning the dreadful silence of those who gathered at Taş Konak about the deportation of the key figures of the Armenian literary community in Istanbul in April 1915.

From bliss to desolation in Davos

The literary gatherings at Taş Konak continued from 1914 until 1918. By this time, after visiting several cities in Europe, İhsan Raif and Şahabettin Süleyman finally decided to visit their old friend Yakup Kadri in Switzerland. Yakup Kadri was having treatment for tuberculosis at the Waldsanatorium (today’s Waldhotel) in Davos Platz. This was a sanatorium built in 1911 at a high altitude for such treatment. Nobel Prize winning author, Thomas Mann famously visited his wife who was also having treatment in this sanatorium in 1912. In fact, it was these visits that inspired his novel, The Magic Mountain (1924), one of the key works of twentieth century German literature.

İhsan Raif (Taha Toros Archive, Istanbul Şehir University Library)

İhsan Raif and Şahabettin Süleyman also checked into the Waldsanatorium for treatment. Soon, when the defeat of the Ottomans in the First World War began to take its toll on their finances, it became hard for them to afford the sanatorium and the three friends moved into a cheaper hotel. This was the time of the Armistice and the beginnings of the occupation of Istanbul by the Allied Forces. Soon, Ihsan Raif’s beloved tutor Rıza Tevfik became one of the signatories of the Treaty of Sevres on August 10, 1920. The poem that İhsan Raif dedicated to his teacher, although written at an earlier date, was filled with harsh criticisms of Rıza Tevfik’s personality, containing expressions like “shame on you” and “may devil see your face.” (Öztürk, p. xii and 166-7). The opinions about those who signed the Treaty of Sevres were similar to the derogatory views about the members of the German government who signed the Armistice on November 11, 1918 leading to the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. In fact, the expression “November criminals” that was used for them signified the beginning of the “stab in the back legend” in Germany that was later used to mobilize support for the National Socialists.

While in Davos, İhsan Raif, Şahabettin Süleyman, and Yakup Kadri tried to forget the disheartening news coming from Istanbul. Since remembering the past was generating melancholy and imagining a future was impossible, like exiles, they were finding consolation in enjoying the present. As described in Yakup Kadri’s memoirs (Gençlik ve Edebiyat Hatıraları), they were riding snow sleds with groups of people they befriended at the sanatorium while enjoying fondue and wine with the local peasants in the neighboring settlements (hameau). They also attended many symphonic concerts, getting acquainted with Mozart’s, Chopin’s music. One of their close friends was a poet from Strasbourg named Bel. When Bel read his poems to them, it reminded them about the literary gatherings at Taş Konak. They were also translating some of İhsan Raif’s poems to French and reading them to their friends in Davos. It almost seemed like their literary gatherings were continuing in Davos albeit with the absence of their friends in Istanbul. Yakup Kadri wrote that he had never seen his friend, Şahabettin Süleyman, enjoy life and its offerings as much as he did in Davos.

Unfortunately, these joyful days came to an end when both Şahabettin Süleyman and Yakup Kadri contracted the notorious Spanish flu in that cheap hotel in Davos. Yakup Kadri survived the disease but Şahabettin Süleyman died in Davos. When they were trembling with bouts of fever and quarantined separately, they lost touch with each another. Their friend from Strasbourg, Bel, was the only person present when Şahabettin Süleyman passed away. Since the news of his death led to the hospitalization of the devastated İhsan Raif, Bel ended up taking care of the burial arrangements for Şahabettin Süleyman. Bel dressed him up before placing him in the cascade and crossed his hands in front of his body. Later, he realized that this was not how Muslims were buried. He told Yakup Kadri that in the absence of any guidance, he did what he thought was best. Afterwards, when Yakup Kadri thought about the bohemian and chaotic life of his friend Şahabettin Süleyman, he burst into both laughter and tears and thought: “Poor Şahap [Şahabettin Süleyman], it seems you have exited to hereafter like a vagabond, against all customs, like the way you entered life.” (Gençlik ve Edebiyat Hatıraları). Until today, there has been no record of the location of Şahabettin Süleyman’s grave in Davos. After long months of mourning, İhsan Raif finally found the energy to make the long trip back to Istanbul. She was accompanied by Bel who would soon convert to Islam, change his name to Hüsrev, and become İhsan Raif’s fourth husband.

İhsan Raif (Taha Toros Archive, Istanbul Şehir University Library)

After the death of Şahabettin Süleyman and her marriage to Hüsrev, İhsan Raif spent most of her time in Europe. There is very little information about the few years that she lived after Şahabettin Süleyman’s death. One letter that she sent from Luxembourg on February 27, 1925 was sent to Halit Fahri by one of İhsan Raif’s relatives in 1965. In this letter, published in Edebiyatçılar Çevremde (p. 217), she wrote: “My ears desire to hear my own pure language. My eyes remain closed most of the time so that I can imagine the place where I grew up.” (p. 217). İhsan Raif did occasionally visit her daughter in the Princess Islands in Istanbul. Hüsrev accompanied her in these visits. In his book about İhsan Raif, Öklü refers to the memory of her granddaughter who said that the neighbors would gather curiously in front of their house in these visits in an attempt to catch a glimpse of Hüsrev who was much younger than İhsan Raif. By this time, İhsan Raif, the once respected host of many literary gatherings, was attacked for marrying a non-Muslim and for not giving her husband a proper burial. She became the subject matter of bitter gossip. In her memoirs titled Bir Devrin Romanı, Halide Nusret Zorlutuna, a female poet and novelist, mentions a letter that she received from Vâlâ Nurettin, a journalist/writer known with the pseudonym Vâ-Nû. In the letter, after underlining what a great man Şahabettin Süleyman was, Vâ-Nû wrote the following: “As much as I liked him, I did not like İhsan Raif. Poor Şahap! [Şahabettin Süleyman] They say that this woman caused her death. What a bad writer. What a bad woman. I have been hearing a while that İhsan Hanım married a young Swiss named Bell or Beli. I do not know why but it really got on my nerves…if you knew Şahap, you would agree with me. Poor man was a deceived spouse in life.” (p. 144)

İhsan Raif died after a surgery in a Paris hospital on April 4, 1926, following a late diagnosis of the inflammation of her appendicitis. Her husband Hüsrev brought her coffin to Istanbul on a ship, in a journey that lasted for over a month. After funeral prayers at the Teşvikiye Mosque close to Taş Konak, she was buried in the Aşiyan Cemetery overlooking the Bosphorus on May 29, 1926. The announcement for her funeral (Akşam, May 28, 1926, cited in Coşkuntürk, p. 39) was like the microcosm of her life. Although she was identified as an honorable poet, she was defined through her relations with men, rather than as a literary persona of her own; namely as the daughter of the late Köse Mehmet Raif Paşa, the mother in law of her daughter’s then-husband Fadıl Kibar Bey, and the wife of Hüsrev who brought her funeral from Paris.

Pen, pillow, and a solitary dialogue

The literary gatherings at Taş Konak came to an end with the death of Şahabettin Süleyman. The literary figures who befriended İhsan Raif through her husband did not continue their relations with her. She was now seen as Şahabettin Süleyman’s widow who failed to ensure that her husband had a proper burial. In their eyes, she was also a woman who married the French poet who gave her husband an improper burial. Her poetry was no longer a topic of interest for these literary figures.

The literary figures who were present at the gatherings at Taş Konak, even at the height of their interest in her poetry, were focused either on her beauty and refined manners or the patriotic themes in her poetry. They put her on a pedestal as a woman and enjoyed watching her refined manners and her competent performance of music. After the publication of her poetry book, Gözyaşları in 1914, the Taş Konak guests who wrote about her poetry mostly emphasized her masterful application of a new syllabic meter to patriotic poems.

Selahattin Enis, who famously read suggestive stories at Taş Konak gatherings, wrote a long and praising review of İhsan Raif’s book Gözyaşları in 1916, at the height of the literary gatherings at Taş Konak. In this review, he wrote: “Those who leave their mark are all different and special…In Gözyaşları, İhsan Raif Hanım conveyed to us the tragedy and sorrows of a nation, the pain and cries of the humanity, tear drops and wishes of life, the autumn and poisons of love…she sprinkled our sinful and ill spirits, that deeply desired and longed for such national and candid tunes for years, with hope, calmness, and consolation.” (cited in Coşkuntürk, pp. 47-49). Selahattin Enis referred to İhsan Raif’s masterful use a new syllabic meter not just in poems of patriotism but also in passionate verses of love. Her passion was also expressed by her tutor, Rıza Tevfik in 1914, who referred to her work as “poetry of fire.” (cited in Coşkuntürk, p. 51). Writing in 1966, another poet of the era, Yusuf Ziya (Ortaç) said that “her pen was as free as a man.” (p. 324) In a piece that he wrote after İhsan Raif’s funeral, Fazıl Ahmet, another regular guest at the literary gatherings, described her as “a pure and pure Turkish woman, a Turkish lady who knew of our national desires.”(cited in Coşkuntürk, p. 47).

İhsan Raif (Taha Toros Archive, Istanbul Şehir University Library)

İhsan Raif, like most women, was regarded as a transmitter of national feelings by the literary men in her gatherings. Nevertheless, her poetry was certainly above and beyond patriotic verses. Her words reflected a deep sorrow about the many troubles that she endured. Many decisions about her life were taken by men, either her father or husbands. Yet, she had her pen and never stopped to use it to reflect the inner conversations of a woman throughout her short life. Her pen accompanied her all through the changes in her life. She never parted with her Notebooks containing her poems. Remarkably, there were also cooking recipes for desserts and advice for skin care in between her poems in one of her Notebooks. (Öztürk, p. 218 and 226). Her writing reflects an inner voice which was the source of her power and resilience. I think, her inner voice was nowhere more evident than in her poem about her pillow (Yastığım). (Öztürk, pp. 90-92). This long poem that is addressed to her pillow contains verses that refer to it as her loyal confidant that knows about her troubles, pleasures, joys, thoughts, secrets, fevers, goals, and desires. The final verses are as follows (the original verses are followed by my translation to English):

Yakınsın sen bana herkesten yakın

Ey, benim vefakâr, sadık sırdaşım!

Ayrılma hiç benden, eskime sakın,

Sen olmasan öksüz kalırdı başım.

You are close to me, closer than anyone

Oh my faithful, loyal confidant!

Never part from me, do not wear out,

If it were not for you, my head would be an orphan.

İhsan Raif was a woman with a pen and a pillow who lived in Istanbul in turbulent times. She remained loyal to her own calling which was poetry. Although her verses inevitably reflected the prevailing political currents of her times and echoed nationalist motifs, she had a lyrical style that was unwaveringly feminine. She strikes me as a poet who engaged in a conversation not only with her peers in the literary gatherings at Taş Konak but also with her inner voice. I think, this was a conversation akin to what Hannah Arendt called “solitary dialogue,” and/or “silent intercourse” in The Life of the Mind. İhsan Raif, first and foremost, strikes me as a woman who engaged in a solitary dialogue. Her life and verses portray that a woman’s use of her pen in a way that reflects such solitary dialogue is a form of resistance that can still empower women a century later.

•

* I am grateful to Ayhan Aktar and Erdağ Aksel for sharing my interest in İhsan Raif’s life, reading the essay, and offering invaluable comments. Needles to mention, the sole responsibility for the contents of the essay belongs to me. All the translations in the text from Turkish sources are mine.

[1] “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Signs, 1/4, 1976, p. 875 (translated from French by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen).