Alexievich: More than suffering

Does the text command us not through its literary force but through the power of real suffering?

14 Haziran 2018 14:25

Why does suffering –from which we try to flee with all our strength when it threatens our existence- affect us, absorb us and maybe even fascinate us when we experience it through the mediation of literature? Such is challenge posed by writing capable of hitting us in a way that feels real. What is the secret of the transformation of our feelings regarding suffering? If we happen to owe this transformation to something like the “aesthetic experience of suffering”, how can this experience be described?

It was Aristotle, the originator of literary criticism- who pointed out for the first time the question underlying all of this: Why would we desire to watch the destruction of the tragic hero? What kind of a pleasure do we get out of this, or what kind of a remedy (moral? medical? psychological?) do we expect from it? Even though his famous formulation of catharsis1 is still a matter of discussion the very least we can say is that his Poetics left Western literature with the following presupposition: Art (of course, particularly tragic poetry according to Aristotle) has the means to bring us into a special kind of contact with the experience of suffering. The ensuing enquiry here aims at an understanding of the nature of this contact: how, in which ways, and through which experiential opportunities does literature make this possible?

The line of reasoning that appears in the Poetics (that, influences Kant and the German romantics) tells us this: that the experience of suffering in an aesthetic context means, before anything else, that a distance -a kind of a distance of imitation- is created between suffering and us. This is to say that suffering ceases being a personal experience and, through the influence of the experience of distance, it leads us to a rather general (maybe even universal) intuition. Art gives pleasure, because it places what we usually tend to call the “real life” at a distance, in such a way that our concrete existence is not exposed to its “real” threats. Of course, this does not mean that suffering, by moving away from us due to the distance in question, is transformed into an object of a detached analysis. It rather means that suffering, and the emotions that it brings along with it, goes through a transformation and leads to a special form of experience (maybe to something that can be called “the aesthetic experience of suffering”).

Besides this distance of imitation, one may also refer to what we can call a “distance of fiction”. This time, our source of inspiration is the distinction that Aristotle makes when he dissociates literature from history: literature is not the imitation of what has happened, but rather the imitation of what has the possibility of happening, and from this perspective it is disassociated from the discipline of history.2 To the extent that it opens us an unlimited space of possibilities (rather than merely representing this or that event), the scope of literature expands from the particular towards the universal. This “distance of fiction” would mean that literature is closer to philosophy than to the discipline of history.

Besides this distance of imitation, one may also refer to what we can call a “distance of fiction”. This time, our source of inspiration is the distinction that Aristotle makes when he dissociates literature from history: literature is not the imitation of what has happened, but rather the imitation of what has the possibility of happening, and from this perspective it is disassociated from the discipline of history.2 To the extent that it opens us an unlimited space of possibilities (rather than merely representing this or that event), the scope of literature expands from the particular towards the universal. This “distance of fiction” would mean that literature is closer to philosophy than to the discipline of history.

This being said, in many cases, the reader’s emotional world does not respect these distances and, bypassing the mediation of art, comes into a closer contact with suffering. In other words, particularly when suffering is itself the subject, this “pure aesthetic experience” may not be possible. Indeed, despite the supposed aesthetic distance, the suffering described in a work of art may start to address us directly and to threaten us implicitly. In plain terms: we cannot but imagine that what we have been witnesses to through literature may one day, somehow, happen to us. If, as Aristotle said, literature covers what is possible and, in this way, hints towards what is general, as a paradoxical consequence of this, we might get closer to suffering again rather than move away from it. In this case, literature is telling s us that suffering is a possibility for all of us. Then the suffering, even in a text of tragedy that has the “highest” literary quality, can emerge as an experience (so to speak, with the vividness of a possible experience) that threatens our concrete existence.

At exactly this point, a text that concentrates on the narration of suffering gets into dangerous waters. The experience of this or that suffering (even when it is a remote possibility) is so real and fundamental that the narration of a torment can be impressive by itself – in a way to wash out the magical effect of the aesthetic mediation. Thereby, the text of literature in front of us overwhelms us, not with the narrative strategy that it uses or the craftsmanship in its tone and language, but only and merely with the power of the suffering that it narrates. The mere fact that the suffering is laid in front of us, just as it is, satisfies us as a reader mainly because it affects us in a deep way -that is to say, it leads to powerful, and even vital emotions. In such a case, because we cannot stay indifferent to suffering, because we cannot give up on the affective / psychological / moral burden that it creates in us, we carry on reading. Maybe the text in front of us is weak as a literary work; however, the power of the events that it narrates compensates for this weakness and drags us through to the last page.

***

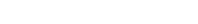

It is hardly conceivable that Svetlana Alexievich’s book Secondhand Time3, which mainly consists of a series of extremely touching narratives of suffering, would not confront such a risk.

The text, which focuses on the period of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the dazzling and mostly agonising transformation stories of that period, and which at the same time goes intermittently back to the years of Stalin (which are full of enthusiasm and dismay), is interwoven with narratives of suffering that sometimes cause in the reader an urge to revolt or a sense of intimidation : The suffering of suddenly meeting poverty and unemployment, the suffering of having to run over the corpses during the war, the suffering of slowly rotting in prison or during exile, the suffering of the mother witnessing the suicide of her own child, or that of the child witnessing the suicide of her own mother… Reading these stories, the reader -playing the devil’s advocate a bit- might find him or herself wondering: Is this terrifically impressive text carrying us away simply with the threat of the suffering that touches all of us as humans and with the striking power of the suffering that it relates to us directly?

Further to that, when “the aesthetic experience of suffering” is the question, there is another factor that makes Secondhand Time so intriguing: The book in our hands has the features of a documentary, since all these devastated people are real. This means that the narrative revolves around true stories that fall within the remit of the historian, and not those possible events that Aristotle assigned to literature. This is a text that is entirely infused with the voice and words of others, except for a few exceptional moments in which the author brings herself to the conversation. Hence, the author’s main activity is to bring to light a large body of lived experiences and to make a montage of them. For this reason, we could think that all this “real” material that we read incites in us a sense of threat that no novel can incite, and that reading the whole narrative with the sentence “what’s more, all of this really happened!” echoing in our minds, the aesthetic distance that Aristotle talks about disappears gradually. Then, the question mentioned above gains even a greater weight: Can this text be gaining its power from the live and even bold presentation of real suffering? Can it be attracting us, not with the power of literature, but with the power of suffering? Can it be that, rather than the literary insights that it creates for us, what connects us to the text is the uneasiness and fear prompted by the fact that these torments have actually been experienced, or that they might be experienced one day, somewhere very nearby to us or in our own life.

When we take into account that Svetlana Alexievich sees herself as a person of literature rather than a journalist (and of course she is the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature), gripping questions -not only regarding the literary experience of suffering, but also regarding the nature of literature per se- arise. We start asking when a text stops being a documentary or historical text and crosses into the territory of literature, and when the narration of facts gains an aesthetic feature (in such a way that the distinction made by Aristotle between literature and history is invalidated). And, of course, we also start to question the role of the “creator” here: in what sense is an author who does not engage in “creating out of nothing” (an author who, rather than inventing new lives, chooses to pick lived experiences as her material and passes them through a minute process of selecting-eliminating-editing) creative? To elaborate, what does it mean that authorship is a “creative” task? What kind of a “faculty” is our much cherished “faculty of imagination”?

Answering all these engaging questions is beyond the scope of this article. Yet, by going through some striking moments of the Alexievich text we have before us, we can try to understand how suffering is covered in it and how it becomes a part of an aesthetic experience. We can thereby try to see how a documentary text may not be satisfied with leaving us only with the threatening feeling of suffering, but also takes us further, to new places.

“May God not let a person live in times of change”

First of all, let us consider the special historical turning-point that Alexievich's text focuses on: the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the subsequent moment of re-establishment. When the great Soviet project, which started with the October Revolution and aimed at the construction both of a new country and of a new human being, ended in 1991 with a tremendous trauma -as one witness said "through surgical methods" (p.54)- a life-changing test began for each individual: the test of change. People submit to the necessity imposed by this period of tremendous change (as if they submit to a natural disaster) and are suddenly uprooted from the existence in which they, in one way or another, dwelled / had tried to dwell: a high rank soldier finds himself behind a stall in a bazaar; the mafia suddenly takes over the old family house in which the family had been thoroughly settled for years, diplomas become rubbish overnight, professions become history, social recognition evaporates. Worst of all, affectionate and beloved neighbours become perpetrators of massacres, enemies or informants. A Russian to whom Alexievich hands the microphone paraphrases the putative Chinese proverb: “May God not let a person live in times of change” (p. 34).

In this broad context, we can say that the moments of suffering that Alexievich’s “characters” experience can hardly be reduced to unexpected blows that strike us from time to time and startle us. The stories that we read are rather like a series of experiences that accumulate through an immense, everlasting narrative of transformation and, as such, they give rise to various sorts of intuitions in us. Perhaps Alexievich’s greatest achievement is that, thanks to the way she organizes the material she has, the testimonies we read get beyond their individual contexts and become the elements of a larger narrative. The existence of this larger narrative, which we can call “history”, constitutes the main power of Alexievich’s text. As she underlined in her Nobel Prize speech, Alexievich’s main endeavour is to write “the history of a utopia” or “the history of the ‘Red’ man”4. (Even maybe, as one critic says, “the history of suffering”5…)

In this broad context, we can say that the moments of suffering that Alexievich’s “characters” experience can hardly be reduced to unexpected blows that strike us from time to time and startle us. The stories that we read are rather like a series of experiences that accumulate through an immense, everlasting narrative of transformation and, as such, they give rise to various sorts of intuitions in us. Perhaps Alexievich’s greatest achievement is that, thanks to the way she organizes the material she has, the testimonies we read get beyond their individual contexts and become the elements of a larger narrative. The existence of this larger narrative, which we can call “history”, constitutes the main power of Alexievich’s text. As she underlined in her Nobel Prize speech, Alexievich’s main endeavour is to write “the history of a utopia” or “the history of the ‘Red’ man”4. (Even maybe, as one critic says, “the history of suffering”5…)

The meaning of this is not that the historical dimension creates a kind of background for the personal one. What we have issue with here is a rather complicated relationship between these two layers, or better, an integral whole that amalgamates them. Indeed, every narrative that we encounter here constantly breathes in and out in the middle of a sequence of dazzling historical events, and this is true even for those moments in which an extremely personal experience of suffering or of quest for happiness is at stake. The reason for this is not that an “author” reminds us of the relevant historical context constantly -as would be the case in a mediocre historical novel. It is rather that the “characters” who talk are, willingly or unwillingly, in direct contact with a broader context, namely that of major historical events and transformations. The history of the Soviet Union, which encompasses (in many cases ruthlessly and even brutally encompasses) all those personal experiences, is constantly revealed in front of us as a larger narrative. Therefore, each individual narrative can live only amidst major historical events (that are in many cases spiralled out of control): The construction of an empire, the Second World War, the end of the Cold War, the 1991 coup attempt, transition to free market, and so on. It seems like each story reminds us of an often neglected reality that keeps surfacing again and again: what is individual is also historical and the petty life of a human being is always surrounded by a much larger field of forces.

“Happy people are like children”

The storms of history… But that’s not all: while reading the book, we do not lose sight of the fluttering of thousands of separate individual lives who maintain their existence amid these storms. History, the history of the Soviets, might be sweeping people up with all of its harshness. However, we do not lose sight of that endless struggle for survival and those unique stories that, no matter what, continue to be lived. Amid this immense storm named history, we never stop reading about people who continue to pursue their own quests for happiness, who try to create their own happy stories and who invent their own strategies for happiness. The stories make us feel that people do not only have a tough adventure with suffering but also with happiness and that, in the end, these two adventures are barely distinguishable. Happiness too, like suffering, shows up as a fundamental life force that has an almost external impact on people, a force that haunts them, sometimes clutches them tightly, and sometimes abandons them. Amid all those dark stories, happiness turns up as an unexpected clarity of memory, generally as the beginning of things, such as the birth of a baby or the genesis of a love. Olga Karimova’s words: “We had happy hours with him, absolutely childish hours. […] Happy people are like children. They ought to be protected, they are fragile and amusing. They are unguarded. […] My mom used to say ‘unhappiness is the best teacher’. People want happiness, you see” (p. 236).

Happiness is confusing and perturbing to the extent that it makes people fragile. It is like an illness that was caught willingly, and yet desired, desired despite everything, almost like an event that befalls one. The truth is that there is not much that one can do with it, or learn from it, or incorporate from it. At most, one can try to retain it. However, whatever one does, the feeling of happiness does not promise much, with the exception of its momentary experience and its future evaporation. Even happiness that was experienced in a gulag -yes, happiness shows up there as well- may find its place in peoples’ lives as something lost. Years later, the ex-prisoner who managed to make a life for himself outside the gulag and ate the most delicious meal of his life in the fanciest restaurant in Moscow, realises that happiness stayed there in the gulag’s boiler room where a miraculous broth was cooked, or in that day when he found some pieces of rubber to patch his boots (p. 242). The unexpected happiness that clutched him tightly at the gulag, left him lonely in the free life outside and stayed in the past at the gulag.

“Embracing the suffering”

Then, perhaps, we are obliged to go back to unhappiness, even to suffering (Karimova’s mother maybe did not say “unhappiness is the best teacher” for nothing). Alexievich’s pages are full of characters who try to experience suffering with a kind of consciousness and make sense of it, turn it into an object of experience and a means of maturation. Characters keep saying to themselves that not happiness, but perhaps unhappiness is the main life-sustaining source. Alexievich said herself in her Nobel lecture: “Suffering is our capital, our natural resource. Not oil, or gas – but suffering. It is the only thing we are able to produce consistently... Even though in Secondhand Time she has almost completely withdrawn herself, there comes a moment when she cannot resist to interfere and says: “I wonder around with suffering, I draw circles. I cannot cross these lines and escape these circles. There is everything in suffering, including darkness, including victory...” (p. 389). It shouldn’t be inferred that we can love suffering, that we can find happiness in it. However, if suffering happened to us once, from that point on we can turn it into a part of our lives; we can own it and embrace it. The words of the author Maria Voyteshonok: “Taking suffering into your hands, embracing it completely and being born out of it, while emerging from it, taking something of it with you. That’s such a victory that there is only meaning in this. Your hands are not empty” (p. 255). Like happiness, suffering also is something that befalls us. However, its major difference comes from our possibility of turning it into something, turning it into a matter of contemplation and thus, creating a new layer of life out of it, reconstructing ourselves thanks to it. 7

***

What this means is that we can at the same time read this whole book as a long and arduous meditation on suffering, in other words, as a meditation on the experience of suffering in general, rather than on the personal experience of this or that suffering… However, the real virtue of the text -the one we find in all powerful literary texts- is that this meditation is not pursued through the direct exposition of a line of thought, but through the mediation of what is personal, subjective and particular (and this, through a montage of the “real” material).

Maybe we can put it like this: As the reader of the text, we occasionally submit to the naked and concrete suffering that the characters encounter. In other words, we go through that threatening and uncanny experience of suffering mentioned in the introduction of this article. Yes, suffering addresses us, with all its immediacy and grimness, as mere suffering, as that major experience that may possibly befall on us one day. However, as we said: that is not all. These stories of suffering tell us more than suffering at many points. Suffering, in almost every page of the text, appears within the cogs of that grand narrative we call history. However, that is not all either: While the cogs of history turn and while they drag what is personal into the big picture containing the masses, people continue to strive to retain the only life that they have, to make sense of it, to pursue efforts unique to themselves for rendering it worthwhile, and to find new strategies for happiness. Sometimes, by refusing the ordinary spiritual map -the two opposite poles of which are happiness and suffering- they continue to accumulate power from the personal experiences of suffering and invent new ways to “embrace suffering”.

“Embracing the suffering.” Maybe we can think of this as a metaphor for our experience of being a reader -at least the experience of reading Alexievich. What Alexievich’s text makes possible for us is to experience suffering in such a way that, without taking it primarily as a concrete threat for us, we can also meditate on it or turn it into an object of intellectual contemplation. Aristotle was clearly wrong: even when a good documentary, a good book of history or Alexievich’s text talks about plain facts, it may very well incite in us some intuitions about what lies beyond “that which happens”; while narrating the suffering, they may reveal to us more than the suffering itself.