“There is a fixation on the new”

Jamie Byng: I think a lot of time and effort is not put into allowing readers to discover the things published in the past. Great books seem to be timeless. We don’t spend enough time as an industry to celebrate this incredible history of literature

03 Nisan 2016 12:04

It’s hard not to be overwhelmed when one Googles you: the bad boy of literature, the most dynamic figure in British publishing, the giant killer – plus a DJ, a marathon runner; and to address you properly, the Honourable Jamie Byng. But, who is Jamie Byng, the reader?

I suppose it all drives from being absolutely passionate about how stories affect people. I am interested in how literature and language connect people; it could be a visual language, a written language, or the spoken word. You probably know that before I got involved in Canongate I ran a bar in Edinburgh called Chocolate City. It was a very important experience for me. I learned a lot and I also enjoyed; it was one of the things that made me realize early on that if you do something you absolutely love, then it suddenly becomes synonymous with pleasure as well as doing something hopefully you do quite well. And it also taught me something really important about trusting your taste and not being too worried about what you think the audience wants to read, or listen to, or dance to, but first of all to remember that what you want to read, or dance to is the thing that matters. Because what else can you trust other than your taste? And hopefully you've got good taste or interesting taste. Look, everybody's taste is interesting to some degree, but some people's taste is more interesting than the others. I've always valued enormously those people who have knowledge and are interested in sharing it, and allowing me to experience things I'd have otherwise never experienced.

What does this have to do with the choices you make each day as a publisher?

I think that's always driven my publishing experience: When I find something that I value, that is entertaining, original, and makes me see the world differently, and makes me see people differently, and myself differently, I do whatever I can to put these things into as many hands as possible. So, I've always felt that passionate energy is the most important thing. You can't really learn taste; it evolves over time if you are curious. And I think curiosity is what I've always admired in other people who don't think in set ways.

You were once quoted as saying, “Books were not the most important things in my life,” referring to the time when you got involved in Canongate. Twenty years on, what is your take?

I've been at Canongate now for twenty-three years and over that period my love and appreciation of literature and of books have only grown and my knowledge of literature has grown. Because I've read more books, I've met more writers, I've learnt more about the creative process. But again, it's absolutely not restricted to books, one of the things I've always wanted to do at Canongate is embrace all forms of expression; so, there are unsurprisingly quite a lot of people on our list that don't think of themselves simply or predominantly as writers. I brought you Terry Gilliam's memoir, which no one has seen yet. Terry is for me a complete creative genius, a fantastic storyteller and he happens to be known as a filmmaker but he is the sort of person I've always wanted to work with at Canongate. It’s not that I don’t publish pure writers but look at JJ Abrams. He is first and foremost known as a filmmaker; Nick Cave is best known as a musician, but he is also a terrific writer; Miranda July, I don't know what she's most known for because she's done a bunch of things, but she is an incredible writer. Gill Scot Heron who had a huge influence on me as a young man, both as a musician, but also as a man who was able to understand complicated social and political situations with incredible wisdom and had an incredible humanity about him; he was really like a father figure to me and we became really close and I published everything he wrote and his memoir later on. I could go on and on.

Is Letters Live another result of trying to think out of the box?

Letters Live embodies the ways in which we have been doing for many years really culminate in a way in a project like that. Because there we have what started as a website evolved into a brilliant book --Letters of Note-- and we started doing these Letters Live events in 2013, bringing in for that first event Nick Cave, Gillian Anderson, Benedict Cumberbatch... And that was all about, again, connecting extraordinary material, in this case letters, to a new format, in this case Live Letters. I think as a DJ that's what you do; you are playing a record made in 1972, so you might be making something public from the past or you might play something recorded in the last year. That's what I did as a DJ; I played a lot of black American jazz, Latin, R&B, hip hop... So, I think all these things have helped to transform my identity as a person but also as a publisher. What excites me the most as a publisher is the quality of the work, and the relevance to an audience and trying to be creative in the way you present it to the world. These Letters Live events, on one level are really good for marketing but actually they became extraordinary experiences. We ended up doing about 13 of these nights now; the latest of which was hosted by Benedict Cumberbatch in Covent Garden in April (2015) where we had over one week sold eight thousand tickets and we had Ian McKellen, we had Kylie Minogue, we had Russell Brand, Tom Hiddleston as performers.

Do you believe such events promote and create a public appetite for literature?

I think they do. I've always been passionate about what reading can do; reading is a form of meditation, a form of prayer; it is an out-of-body experience, you are made to feel like how someone else could feel, as most greatest writers emphasize that's how empathy is created between humans. But, and that's why I've always been interested in film, in music, and all these formats, because they enable it being communicated from one person or a group of people to a larger group. So, I like to think that Canongate will continue to always experiment, innovate and join more and more things and make more and more connection between things that aren't always necessarily connected.

Referring to the time you took over Canongate, you say, “A good ten year-old could tell I didn't know what I was doing.” Today, Canongate is hailed as one of the most significant independent publishers in the UK. Looking back now, did you really have no idea what you were doing? Did you learn everything on the job?

I am still learning. If you ever think for a second you understand fully what you are doing or what you are capable of doing, then you've not learnt one of the most important lessons there is. There is no question I had very little experience when I got involved in Canongate, but that was perhaps a fortunate thing. I didn't know how things were supposed to be done. I wasn't told this was the way to do things. I've learnt so much from other people, but that's because I've wanted to learn. As long as you appreciate how little you know, you are much more likely to learn. I don't really distinguish between life and work; I just do what I do; it just so happens that sometimes I am in an office. But I am living and breathing what I do, whether I am cooking, or reading a book, or talking to colleagues. I don't really compartmentalize my life.

I am still learning. If you ever think for a second you understand fully what you are doing or what you are capable of doing, then you've not learnt one of the most important lessons there is. There is no question I had very little experience when I got involved in Canongate, but that was perhaps a fortunate thing. I didn't know how things were supposed to be done. I wasn't told this was the way to do things. I've learnt so much from other people, but that's because I've wanted to learn. As long as you appreciate how little you know, you are much more likely to learn. I don't really distinguish between life and work; I just do what I do; it just so happens that sometimes I am in an office. But I am living and breathing what I do, whether I am cooking, or reading a book, or talking to colleagues. I don't really compartmentalize my life.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve heard people say, “These are tough times for publishing.” Will you second that? I have a feeling you won’t.

Well, it doesn't get easier. And it is tough, but I don't think it's ever been easy, you know. I don't think it's ever been easy doing anything interesting. If it were easy, it'd just be boring. But I feel more excited now doing what I do than I did at any point, because opportunities have grown. Again, that doesn't make it easier, but at least there are more opportunities, there are different ways in which you can try to bring new and interesting ideas to a larger audience. The digital age allows you to do all sorts of things and keep your work interesting. There are fewer gatekeepers preventing you from connecting directly to a larger audience; let's say you have five million Twitter followers. Suddenly you become a very powerful mouthpiece, recommending things and making people aware of those, to challenge corruption and the status quo. Not that I think democracy is particularly healthy in Britain, and American democracy is even more corrupt. You could probably say the same thing for Turkey.

So, what is a publisher to do in face of all this corruption and hypocrisy?

No one on their own can stand against this. One of the films that I've watched this year that's had a huge effect on me was Amir Amirani's We Are Many. It's a very powerful and important film, I think. It's been nine years in the making and it tells the story of the global anti-war movement, the global protests against the second invasion of Iraq, and at the same time it tells the story of how Bush and Blair knowingly misled the population, the Security Council, and Parliament. What I love about it is that it reminds you that even though there are very dark forces in this world, a small number of people can make material change; I think one has to hold onto that hope and that belief. The amount of corruption and hypocrisy is unbearable really, if you think about it. We published a book earlier this year called Gun Baby Gun by Iain Overton, and it talks about the ecosystem of guns around the world. There are six countries in the world that produce more than 70% of all handguns and there is no or very little legislation to prevent the damage they cause. Weapons of mass destruction were the supposed justification for invading Iraq; but the amount of damages these handguns cause is unbearable. Nearly one million Iraqi civilians were killed. That is a war crime in a scale that is so large and it is unbearable that neither Bush nor Blair were brought to account. Now, when someone like Amir Amirani shoots a film like this, he knows very well that he can’t simply change the world, but he can, and that’s what he does, shed light on and illuminate us all about all these hypocrisy, and corruption, and all these systematic lies.

And that is what you are doing as a publisher?

Exactly, you are playing your card to contribute to conversation. I am not, as a publisher, interested in putting out bubble gum stories. I am not judging them in any way; it’s just that I am not interested in them. As long as there is a market for that, that’s fine. I do wish less of these books were published, because of these, I feel, more interesting books are not published.

But what about fiction and nonfiction? Do you see a hierarchy between, say, Gun Baby Gun and Under the Skin by Michael Faber, between fiction and nonfiction, or poems and novels?

No, never. Of course I understand what the division is between a work of poetry, or a novel, or a piece of narrative nonfiction. I came across a quote by EL Doctorow, whose Ragtime is absolutely a masterpiece, where he says “There is no fiction or nonfiction; there is only narrative.” Whether you call it a work of fiction or nonfiction is really immaterial. You know, Picasso says “Art is a lie told to tell the truth.” If you believe that, and I do, it becomes irrelevant whether you call a certain work a work of fiction or not. But what excites me most about poets and novelists is their use of language. They have more freedom in a way as a poet, as a novelist in their use of language. I don't want to make generalizations because there are some nonfiction writers who use language with an incredible and rare imagination. I've always been categorically drawn to fiction than nonfiction; but for the last three years I think that has changed, and it's the same for Canongate; it used to be predominantly what we call fiction and now it's predominantly what we call nonfiction.

Earlier, talking about “tough times,” you actually mentioned the very landscape that makes times tough for almost everybody. I am also curious to learn how you compete with the big players in publishing.

The industry is dominated by a smaller number of bigger and bigger players; and that comes with its challenges, but that also comes with its opportunities. Just because you are small doesn't mean you can't be as inventive, or as creative, or have a high level of quality control. You don't have as much financial resources surely, but in many ways, that can be a good thing. We always try to be bold in what we do; again, big companies can be just as bold, I have a huge amount of respect for big publishing companies. But they aren't capable of being as creative as a small company. They are much more rigid in the way that they are operating with writers and creative people within their body; so, I think we are in a position to be more creative. It's not because we are small that things are difficult right now, they are really difficult for the big houses as well. The margins that publishers give away to booksellers is higher, so it's getting more difficult to publish certain books. But then, with the digital, there are even more opportunities.

The industry is dominated by a smaller number of bigger and bigger players; and that comes with its challenges, but that also comes with its opportunities. Just because you are small doesn't mean you can't be as inventive, or as creative, or have a high level of quality control. You don't have as much financial resources surely, but in many ways, that can be a good thing. We always try to be bold in what we do; again, big companies can be just as bold, I have a huge amount of respect for big publishing companies. But they aren't capable of being as creative as a small company. They are much more rigid in the way that they are operating with writers and creative people within their body; so, I think we are in a position to be more creative. It's not because we are small that things are difficult right now, they are really difficult for the big houses as well. The margins that publishers give away to booksellers is higher, so it's getting more difficult to publish certain books. But then, with the digital, there are even more opportunities.

Was it with this search for creativity in mind, that you’ve redesigned your web page and renamed it as Canongate TV?

Well, the very essence of publishing is making something public; that's what writers do, that's what a DJ does, that's what a filmmaker does; you are taking the stories you are working on and you are taking them to the world. Today we can make a film, and show a film, and upload it to the net, and anyone around the world with Internet connection can see it; so we can do today what we couldn't do thirty years ago. With a certain book; we are broadcasting it as a book, as an audio, as a film, and it ends up being something much larger than a book. That's what I think of publishing. You don't know what these ways are going to be when you first read a book, nor should you know. If you have a clear idea of what you are doing, then you are actually going to limit what you are going to do, and it means you are not being as creative.

Let’s talk about World Book Night. When you initiated the project, there were a lot of concerns that the project would absorb little bookstores. What good does it do to give out books free of charge?

I give out books all the time. To me, the most important thing is reading. Literacy, though not restricted to reading, is essential to make the most out of life. Literacy should be a fundamental right. World Book Night was really about trying to encourage people who don't necessarily read or who don't read for pleasure. Literacy really begins at home. Books are important to literacy and literacy is important to society.

How did the project start?

World Book Night was born out of a crazy idea. It was inspired by a book by Lewis Hyde, The Gift, that I was given as a gift by Margaret Atwood. We bought the rights, and we published it in the UK, and I gave it to lots of people before it was published. I got great quotes from Zadie Smith, Geoff Dyer, and Margaret Atwood. And the book was published pretty successfully in hard cover, considering it was twenty-five years old. We sold about ten thousand copies. And as we were talking about paperbacking it, I said to colleagues "What if we gave away the book?" and we did. It was so great to just give out books with no sense of expectation; it was actually exactly what Lewis Hyde talked about in the book. Actually all art is a gift, music is a gift from the musician; there is a market economy, but the gift economy is actually much older, and very important to art. That was one of the things on my mind: what if we gave out these books on a massive scale? I was at a book conference talking about ways to make it more relevant for more people to read in adulthood, and I said, "You know what we should do? We should give out one million books to one million people in one night?'' And we did. What happened was, we gave out one million books in one night to complete strangers, and that night one million people actually did have conversations about books. There were some concerns from some people, that it would exhaust the book market. But the truth is if you can encourage more people to read, in the long term that means you are going to invite more people to our industry. Because the more people read for pleasure, the more people will buy books in the long run.

You were talking about making ideas and expression public, but when it comes to publishing, you go by “less is more,” right? Canongate did announce its plans to publish no more books than thirty per year; can you reach that goal?

I hope that's the case. I think we are going to publish about thirty-five in 2016, and maybe it will be down to about thirty-two in 2017. I am really certain that for us to thrive, as a publishing house, requires that every single book that we publish, we publish with a huge amount of care, attention. If fewer books were published by our industry, they'd be published with more care, and more people would read books, because the quality would be much higher. There are some books that we've published that when I look back, couldn’t honestly say, "You must read this! I promise, this book will change the way you think.” I think every book you publish should be like that. I hope we'll continue to raise the bar, continue to be bolder, more daring, more imaginative. And to be able to do that, you've got to have fewer books, because the amount of care and hours we can put into a book is limited. And I am more interested in, alongside the traditional publishing, which we always do, things like Letters Live, collaborations between different countries, and be more ambitious in the way we publish our books. It's not the lack of ambition on our part to limit the number of books, but it's because of the need to be more ambitious.

What is your stand on self-publishing?

I have nothing against it. I think it's great in a way that a new vehicle has arrived for people who have written something and they want to share it with the world. The vast majority of books that are self-published are read by almost no one. So, in terms of the impact they make, they are very minor. Some of the self-published books have gone into the mainstream with traditional publishers coming on board; EL James' Fifty Shades of Grey was such a case. I am not in any way against self-publishing, or judgmental about it; it's just a part of the landscape out there. I don't think the quality of many books that are self-published is really high, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't happen. I find it interesting as a phenomenon, but I don't think it has any bearing on our business.

How essential should it be for a publisher to go after the next big thing? Does a publisher have a responsibility to reprint certain books and build a backlist?

What is essential for a publishing house is building up a significant backlist; whether you are small or big, it gives you financial stability. They give you the kind of base and stability then to invent more writers, and create new things. But, I think it's also important to reissue books that are no longer in print. Part of your job as a publisher is to bring out new talent, new books, but I also think often a lot of time and effort is not put into allowing readers to discover the things that were published in the past. If a book is a hundred years-old and it still resonates, then there must be something really interesting about it, and it's most likely that a book published now will not be read from hundred years now. Writers fall in and out of favour; some books do cease to be relevant. Great books seem to be timeless. I think we don't spend enough time as an industry to celebrate this incredible history of literature built up over centuries, because there is a fixation on the new. I think you have to find the balance.

Just because it’s new does not mean it’s better...

I've always been fascinated by incredible material that is often ignored at the expense of the new. So, when I first took over Canongate in 1994, one of the first things that I started doing is to focus on and put a lot of time and effort into buying the reprint rights. So, I was always thinking well it doesn't matter when these books were created; it matters whether they are still relevant to an audience. To me it was a very exciting revelation that as a publisher there are books out there that I've never heard of and then I was lucky enough to get into, talked into by somebody; and then if I haven't heard of them and other people have never heard of them, publishing neglects them.

I've always been fascinated by incredible material that is often ignored at the expense of the new. So, when I first took over Canongate in 1994, one of the first things that I started doing is to focus on and put a lot of time and effort into buying the reprint rights. So, I was always thinking well it doesn't matter when these books were created; it matters whether they are still relevant to an audience. To me it was a very exciting revelation that as a publisher there are books out there that I've never heard of and then I was lucky enough to get into, talked into by somebody; and then if I haven't heard of them and other people have never heard of them, publishing neglects them.

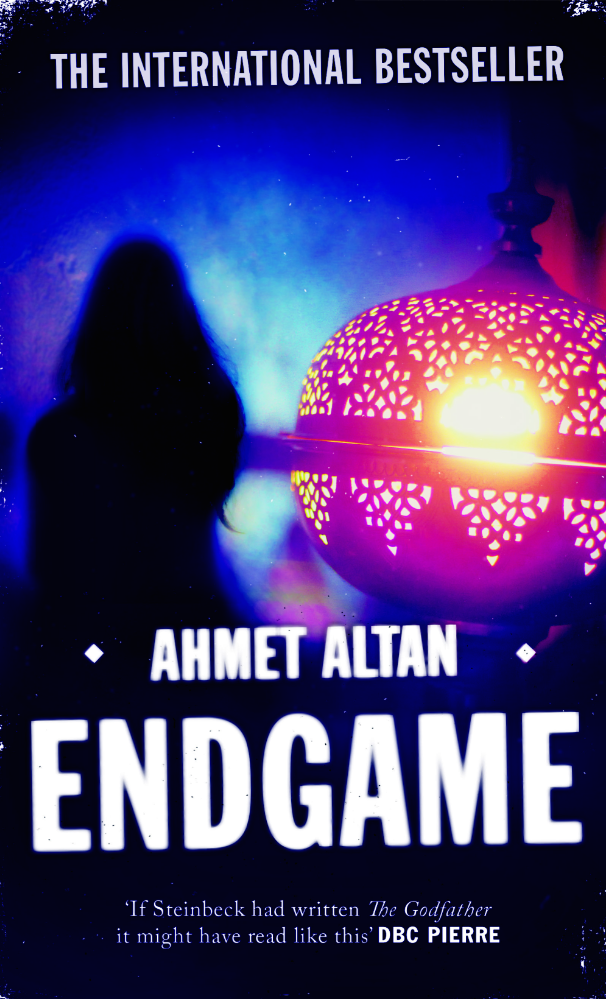

You’ve published Endgame by Ahmet Altan, who happens to be the first writer you are translating from Turkish, right?

He is. And what a way to start is all I can say. I think Endgame is a remarkable novel; and it's remarkable for a lot of reasons, but one of the things that I like about it is that it manages to be both a very serious, philosophical, existential work of literature and a very playful one, has a wonderful sense of humour. I think it resembles a Patricia Highsmith kind of psychological thriller. It has that kind of really dark, intriguing, genuine sense of mystery within it. A great writer is bewitching you. And I think Ahmet is an alchemist and a sorcerer, really funny too, but also very serious, and profound. I think it's a very challenging book as well; it made me think a lot about my life, what's going on and how you live your life. We publish books from a lot of languages, but he is the first Turkish writer to be published by us. But I think less of Ahmet as a Turkish writer, but more as a great writer.