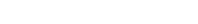

Turkish Kaleidoscope: a graphic novel on the 1970s

"Turkish Kaleidoscope is an oral history of the past. It is also, in some important sense, a pre-history of the present moment."

20 Mayıs 2021 15:30

Turkish Kaleidoscope is, above all, a tonic for nostalgia. A graphic novel on the 1970s might sound like it will cater to those swept up in the revival of the era’s art and music, but this book is concerned less with what’s been rediscovered as with what is too painful to remember. Here is Turkey as tinderbox, where university lectures, trade-union meetings and even the bus ride home are moments away from ignition. It depicts a time when the state had a monopoly on most things but before violence was one of them.

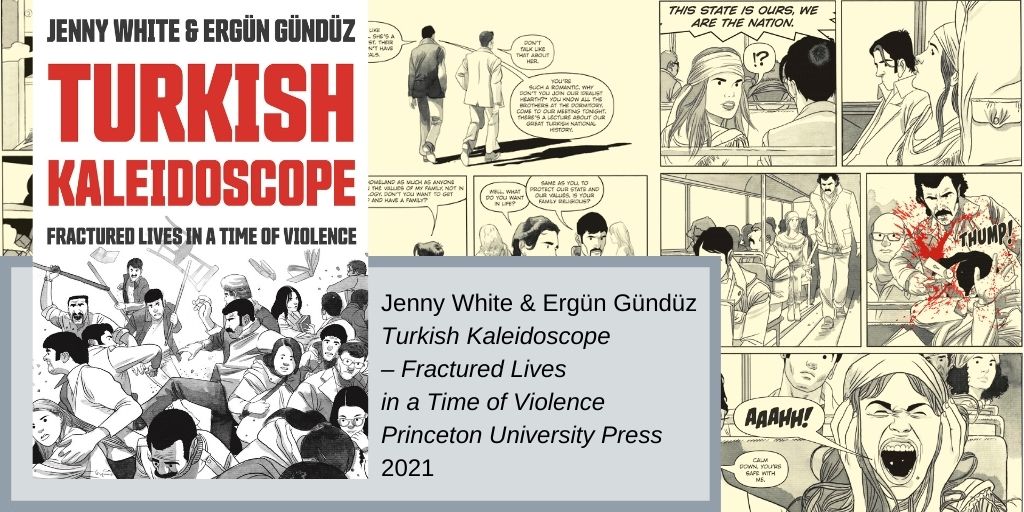

Following almost a decade after Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks, it is the first book since 2012 of Jenny White; anthropologist, novelist and now graphic novelist. Aided by the talented illustrator Ergün Gündüz, her newest genre does a very effective job of portraying violence: an obvious asset when the subject is student politics of the 1970s. Each new frame features a BLAMM or a CRACK, but comic-book conventions can’t dull the shock of so many stones, chairs and punches thrown. As they grab and hurl whatever's to hand, it feels like the country is coming apart in these warring youths’ grip.

The bloodshed between these pages is perpetual and unrelenting. It is also senseless: to borrow from well-known tunes of the time, the tone here is not so much silah bizim, şan bizim as adaletin bu mu dünya? Where idealism does appear it is a destructive lure, turning students into fodder for conflicts they — and perhaps no one — can control.

White first moved to Turkey in 1975 and supplements her own recollections of that time with dozens of interviews on which her protagonists —two leftist, two rightist— are based. That makes Turkish Kaleidoscope an oral history of the past. It is also, in some important sense, a pre-history of the present. Because 1980 so often gets treated like the Year Zero of Turkey’s contemporary politics, the book testifies to what was lost after the coup and (more unusually perhaps) to what, for some, was gained.

Each political age throws up its own reasons why the stories between these pages need retelling. In White's handling of the 70s, our selective and collective amnesia about those times suggests itself as one of the things underpinning today's common lament that things can’t get worse. At times it feels like she is seeking to remind us that things can get, and have been, worse. Those inclined to see their politics half-full may read into this book's bleaker moments a twisted kind of optimism about the present day: to years of unrelenting stasis, compare the futility of revolving-door governments! If today’s politics works for the right and not the left, well, we might conclude… at least they work for someone.

I do not believe White intends us to pick sides between the lesser evils of then or now, still less of right and left. Her method is one of instructive juxtaposition and its result, to complicate these poles. Yet, there is something about the asymmetry of today’s politics that might make the even-handedness of this book’s treatment of those times unpalatable, for some; especially when the final page seems to centre the project of explaining conservative resistance to popular movements like Gezi, by grounding that opposition in memories of the instability of the 70s. There is a risk that the book’s determination to give both sides of the spectrum a fair hearing will end up pleasing nobody, but it is a risk the author is prepared to run. Her boldness is to be celebrated. The same readers don't often get to hear from the left and the right, and rarer still from so careful a chronicler as Jenny White.

•

Pictures are excerpted from The Turkish Kaleidoscope: Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence by Jenny White © 2021 by Jenny White. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.